For Speechwriters, the Struggle Is Real (and It Always Was)

June 13, 2023

A time capsule from almost two decades ago reveals leadership communicators' troubles are stubborn—and their profession is timeless.

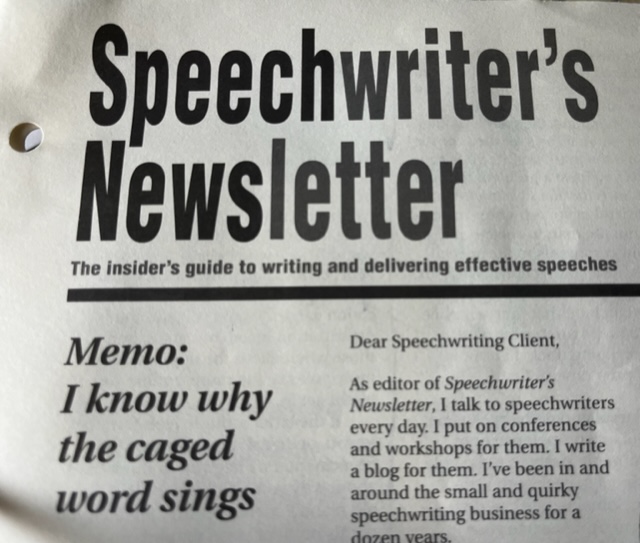

Digging through some old files, I came across an issue of a long-defunct publication I once edited for Ragan Communications, called Speechwriter’s Newsletter. I wrote the cover piece in the August 2005 issue. It’s titled: “Memo: I Know Why the Caged Word Sings.” It’s billed as “an open letter to speechwriting clients everywhere on behalf of speechwriters everywhere.”

Here are some bits of it, along with a few insights I gleaned from what’s changed in this executive communication over almost two decades of tech revolution and socio-political upheaval—and what has pretty much stayed the same.

My first advice for speechwriting clients was to think of speechmaking more strategically.

Just as you don’t buy or invest capital willy-nilly, hire the first employee who shows up for the interview, or spend advertising money based on which magazines and TV shows you happen to watch, you shouldn’t agree to waste your time and your speechwriter’s time delivering speeches that amount to “favors.” It may feel like an easy favor to your board members, your fellow alums, your mentor from your first management job 20 years ago to show up and give a little talk to their group. But the little talks add up and before you know it, you’re giving so many little talks, you and your speechwriter have no time to think about the big talks: the ones that cary important messages to key constituencies.

I asked speechwriting clients to “ask yourself two questions when you get a speech request (or when your speechwriter comes to you and suggests a speaking opportunity). No. 1: Is the audience relevant to the long-term future of our organization? No. 2: If so, is there anything I could say to these people that could change the way they think about our organization or our industry—or either’s place in our society? If the answer is no to either question, don’t give the speech.”

That holds up as far as it goes, though I’d add that changing people’s minds is harder than it’s ever been, and it’s now a legitimate purpose of a speech to solidify or deepen good relationships with important constituencies.

Also? I’m so glad executive communication has broadened to include a dozen other communication vehicles beyond speeches. I still consider speeches and other coherent texts to be the intellectual core of a healthy exec comms operation. But certainly not the only tool, which they still were in 2005—before anybody ever heard of LinkedIn, Facebook, YouTube or Twitter.

Access was the issue then. It’s less of an issue now.

“Your speechwriter won’t complain to you that she doesn’t get enough access to you,” I wrote. “But boy, will she complain to me.”

I went on to ask the speechwriting client to give a speechwriter the following, as a minumum:

• Spend 10-20 minutes thinking, alone, about the topic.

• Then schedule your meeting with the speechwriter. Give this meeting a half hour, so the speechwriter has time to absorb and react, and both of you can amplify the idea.

• Answer your email from the speechwriter when, after having done some research, she sends you a slightly modified speech outline.

That’s it. Really. That’s all you have to do on the front end. And how much time did it take? It took one hour. And if you don’t think it’s worth one hour of your time to prepare a talk, you should probably not be giving the talk. (See “Strategy,” above.)

That section might have seemed naive even then. It surely seems so now. “Thinking, alone”? Srsly? These days we’re lucky if the speechwriter has such embarrassments of time and privacy, let alone the client. In fact, we’re lucky if an exec comms operation employs someone called a “speechwriter,” at all. But they should.

Next, I told this straw client that actually, there was more to do on the speech once it was written. An oral reading of the speech, and a bit of editing. “Return your comments with the following note: ‘This looks good. I’ve got just a few changes.’ As long as you include that first sentence, ‘a few’ can mean up to an hundred.”

Then I informed the client that rehearsal will be necessary. “It is not a sign of cool, of competence or of manly or womanly strength to be able to deliver a great speech with little preparation. Rehearse your speech until you feel you’ll be proud to deliver it to the audience exactly the way you just delivered it in the bedroom mirror.” Minimum, three run-throughs of a 20-minute speech. Making the whole time invested in the preparation for the speech two and a half hours, soup to nuts.

A calculation I didn’t make, but do here: Say your speech is 20 minutes. Say there are 200 people in the audience. Giving that speech, you’re costing humanity 4,000 minutes of its time. That’s more than 66 person hours that could be spent doing something more either productive than listening to your speech, or less productive. If you won’t spend a couple of your own hours in hopes of avoiding a true time-management calamity—what in the world is the matter with you?

I concluded with a point that does seem every bit as relevant as it was before we ever heard of Obama, Twitter, Trump or the Kardashians.

It is my long observation, there are two kinds of speakers in this world: Those who believe that energetic, candid and provocative public speaking and other forms of communication can truly help you and your organization meet your goals, and those who believe the opposite: The more you say, the more trouble you might get in.

If the later attitude feels familiar to you, on behalf of the world’s speechwriters, I beg you to think hard about why you feel this way. Did that old management mentor convince you of this point of view? Or perhaps you got burned for saying too much and never forgot what you told yourself afterwards: I should just keep my mouth shut.

In either case, you need to rethink your attitude. If you’re ever going to help move your organization forward through oral and written communication, you’re going to have to put yourself out there, take risks with what you say, anger someone along the line and make others nervous. …

And if, on the other hand, you’re the kind of speaker who does think what you tell your employees, your customers, your investors and the world at large can move the organization forward, then give a litle more of yourself over to your speechwriter, who wouldn’t have passed this memo on to you if he or she didn’t want, more than anything, to help.

Now in 2023, I and the faculty at the twice-annual Speechwriting School still help speechwriters figure out to get access to the speakers they serve—and how to muddle through without it. Through the new Executive Communication Council, we’ve identified and celebrated many organizations whose leaders believe in communication—and through the Executive Communication Awards, shown off the incredible things that great leadership communication can achieve.

But to a great extent, we are—all of us—pushing the same goddamn rock up the same goddamn hill. And as discouraging as that is, it’s a little bit comforting, too.

It means our work is timeless. Which may be as reassuring at the dawn of ChatGPT as it was at the dawn of social media.