Corporate speechwriting, then and now

February 26, 2021

A 1986 book portrayed speechwriting as a meaningless, Kafka-esque nightmare. Is it a relic of the past, or was it a prescient prologue?

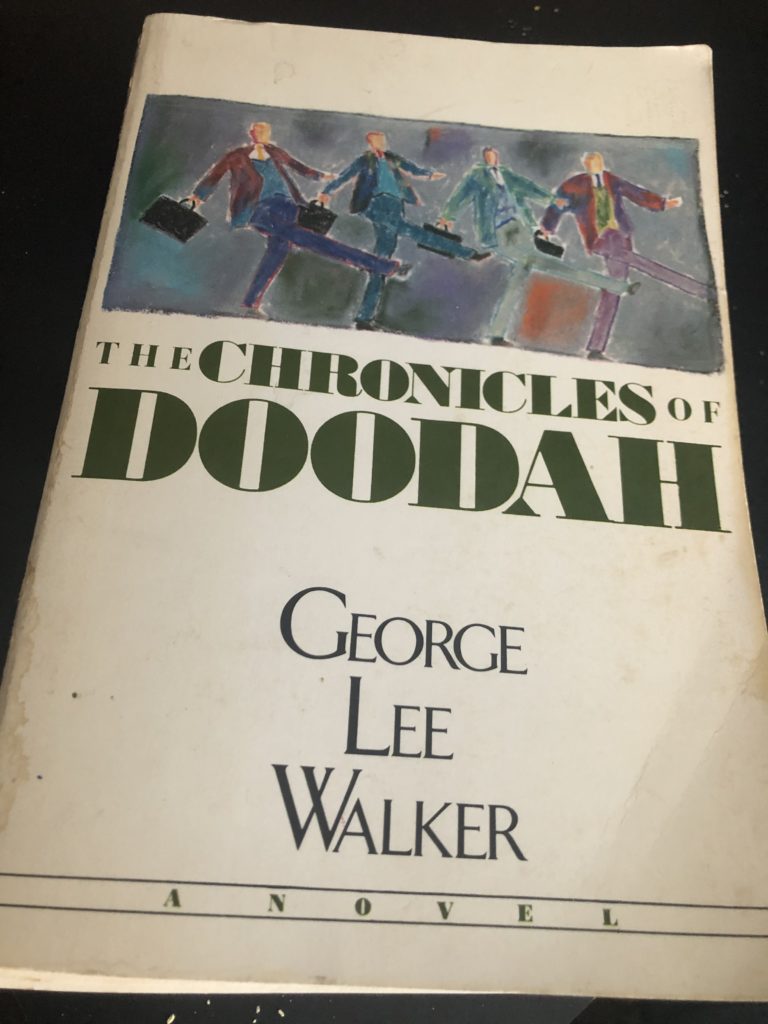

By the time he wrote his novel, Chronicles of Doodah, George Lee Walker was one disillusioned speechwriter.

Having worked for Michigan Governors George Romney and William Milliken, President Gerald Ford, Ford Motor Company president Lee Iacocca and American Motors chief Gerald Myers, Walker had had his fill of a lot of things—corporate life and corporate speechwriting, most of all.

I recently picked up the 1986 book to read as a relic of its time—as a marker of how far speechwriting and corporate leadership communication may or may not have evolved over a generation.

Well, Walker’s bitter and somewhat adolescent caricature of corporate life as an utterly meaningless Kafka-esque nightmare makes this an unreliable time capsule. Indeed, the pages—which have sat on my shelf since I started it and set it aside sometime in the early 1990s—crumbled off the spine as I turned them.

Still: I found Walker’s portrayal of speechwriting back then worth discussing for its similarities and contrasts with modern speechwriting life.

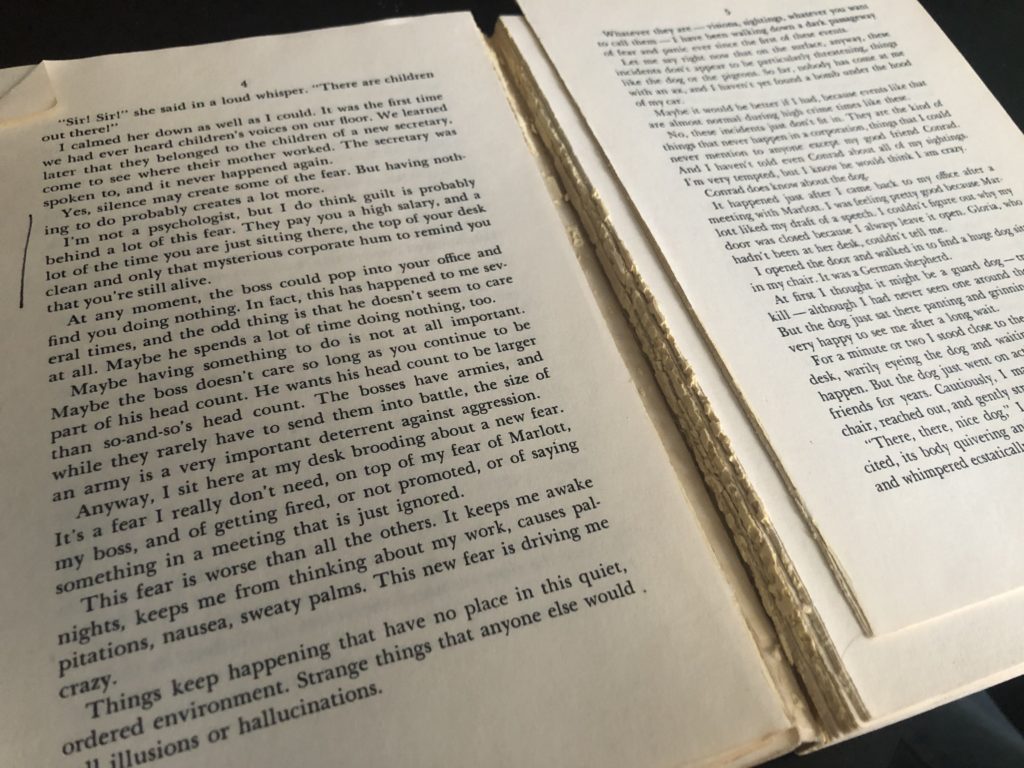

As the book opens, the nameless protagonist, a speechwriter at a huge company in an unidentifiable industry, finds himself sitting in his hushed office with far too much time on his hands, to ruminate on the source of his gnawing fear. “Yes, silence may create some of the fear. But having nothing to do probably creates a lot more. I’m not a psychologist, but I do think guilt is probably behind a lot of this fear. They pay you a high salary, and a lot of the time you are just sitting there, the top of your desk clean and only that mysterious hum to remind you that you’re still alive.”

When the assignments do come, they’re hardly worthy of the speechwriter’s mind or his heart. “Junk, useless stuff,” the character describes the speeches he writes. “Speeches for groups of businessmen attending conventions, or Rotary clubs, or economic clubs of this city or that. The audience is made up of a lot of businessmen. Quite a lot of them give speeches, too, so there is a kind of cross-fertilization, a lot of repetition.”

He continues: “All the speeches are about the same length, twenty to thirty-five minutes. They cover pretty much the same ground, too—economic forecasts, the state of the industry, a description of the Company’s activities, and so forth. You don’t read much about them in the newspapers or hear about them on television because—to be quite frank—they rarely say anything worth reporting. … For the most part, these speeches are dead at the moment they are given. The fact is, they’re dead even before they are given. If you went to hear one of them, you would see some of the audience rush up to the speaker after the speech. They stand there congratulating him on his incisive observations, or original thoughts, or worthwhile suggestions. But we know they do this only for political reasons.”

Why are the speeches so dull? Because “you can’t write anything remotely political. You can’t write anything that might be considered offensive to stockholders or unions, or women or minorities, or other businessmen or farmers or teetotalers, or just about anybody you can name.”

At one point, struggling mightily with a speech his boss has arbitrarily deemed important, our hero consults with a corporate oracle—a speechwriter emeritus who once wrote for the company’s venerated founder. “You’ve got a problem,” the elder scribe tells him. “The fact of the matter is, it’s all been said. Everything.”

In the course of the book, our man complains about the speech approval process, and also about the lack of access he gets, to the Chairman and other execs. People, he writes, “seem to think that the man who writes the speeches and the man who gives them have a very close and informal relationship,” he says. “They have this picture of us pacing back and forth together in deep philosophical discussion, arguing, making jokes, refining points, discussing the meaning of words. Well, nothing could be further from the truth. The fact is that we rarely see our so-called clients. We can write the entire speech from the first draft to the last without seeing them at all.”

For this pre-internet speechwriter, there’s not a lot of external intellectual stimulus, either. “Every morning, the tide of office mail brings an assortment of company communications—reports, memoranda, changes in orders, and new regulations. Tasteless stuff, although it occasionally contains some nourishment. I ingest it slowly, hoping for something new and different. Once or twice a week I receive a telephone call.”

So he’s left to consult with his communication colleagues, who don’t help much either. “‘How about corporate responsibility?’ suggests Honigman, the most junior speechwriter and the one who is always the first to volunteer. ‘We could take Schwartz’s famous speech on corporate responsibility at Yale. That’s one of the five greatest speeches in the Company’s history, you know. We could update it with some of the current social data and provide some really valuable new insights that can get us a good deal of favorable attention …”

They settle on a speech titled, “The Future Is Tomorrow.” The Chairman intones …

What message do I have for you folks today? It is a message of importance, a message for history, a message written on the wind, a message carried on the soul of humanity through eons of history. The message is hope, the hope of mankind, the thing that keeps each and every one of us going, the thing that provides the fuel of progress for Spaceship Earth. What is this message? It is a simple message. A timely one. A timeless one. It is simply this: the future is tomorrow.

Another thing our beleaguered speechwriter didn’t have, it seems, was other speechwriters to talk to. There was no Professional Speechwriters Association in George Lee Walker’s time, nor any reliable way for speechwriters to commiserate. In the book, the only connection with communication peers outside this company is a bad one: The speechwriter’s boss attends “a three-day public relations seminar in Phoenix,” and returns with a misguided make-work scheme “to give the whole speechwriting operation some class”—the requirement that every speech first be written as a one-page “précis.”

The term “best practice” doesn’t appear in the book because it hadn’t been popularized yet. Nor does “executive presence.” Though the speechwriter does find himself in remedial training for “Executive Voice,” and “Executive Mystique”: “the projection of confidence and control.”

Toward the end of the book—after the speechwriter has survived a surreal business trip that involves booze and seduction, and also a mind-bending corporate retraining program—the speechwriter is promoted, and suddenly begins to come around to see the larger purpose of corporate speeches.

Watching the Chairman deliver his words during a speech rehearsal, the speechwriter concludes that, though the words he has written are meaningless in and of themselves—“Doodah,” is what his colleague calls their content—“The important thing is that the Chairman of one of the largest corporations in the country will be standing up before a thousand land surveyors, their wives, and girlfriends, uttering various slogans and ‘thoughts’ between outbursts of music and bright images exploding on oversize screens. Surely the very appearance of this important man will inspire everyone in the audience. Surely some of his wisdom, his power, his competence, will flow out to every corner of the room, and everyone there will leave the room more powerful, more competent, more understanding of the problems of the free marketplace than they were when they arrived. The whole event will be a combination revival meeting, political convention, rock concert, and dinner theater—a ritual not easily dismissed or soon forgotten.”

I told you it was bitter.

I thought to track Walker down, to ask him how he felt his book had aged—and what he thinks it has to say to leadership communicators now.

But it’s left to us to do that, because he died a year ago today—February 26, 2020.

So, let’s.

How did you feel, reading this piece: Sorry for Walker’s beleaguered speechwriter, or sorry for yourself? Angry at Walker’s simplistic portrayal of subtle corporate messaging, or doubtful of the meaning of what corporate leaders are saying now?

Working speechwriters react

I ran this post by a number of speechwriters yesterday to get their reaction to, and several found Walker’s book more familiar than shocking, one writing, “It was relevant then and it still rings true. … This book is dark, brilliant satire that’s also borderline documentary.” Added another, “Isolationism and echo chamber seem like pretty contemporary thoughts to wrestle with to me.” And a third said, “I’m mostly struck by the sameness of ‘doodah’ speak now, just using different terms like ‘transparency’ … ‘thought leadership’ … and ‘authenticity.’”

All legitimate sentiments, to which a fourth corporate speechwriter, Shell executive speechwriter Lech Mintowt-Czyz, responded with what will be the last word, for now:

When I was a training to be a journalist in the unglamorous surroundings of Preston, in the drizzle-soaked north-west of England, our lecturers arranged for us to have a visitation from a VIP. We all gathered in a lecture hall, around 25 of us, and settled down to listen to the then editor of the Sunday Mirror.

I’ll be honest. I didn’t think much of the Sunday Mirror. I thought of it as a raggy rag: a lesser light to The Sun and its Sunday sister paper, the now extinct News of the World. To imagine my view of the Sunday Mirror, think of a tired, limping, British version of the New York Post.

So, the truth is that I didn’t expect too much from the hour I was due to spend in the company of Colin Myler.

What can I say?

I was young. I was ignorant. I was wrong.

He was great, and I left with three incredibly valuable things. First, the certain knowledge that I didn’t know as much as I thought I knew. Second, the first stirrings of my deep appreciation for writers who communicate well with a very limited palette of words, as tabloid writers have to do. And, finally, the best bit of career advice I ever got.

I asked Colin Myler, when we came to Q&A, for the best advice he had ever received as a young journalist. Without hesitation he replied: “Never allow yourself to become cynical.”

That hit me between the eyes. Because if there is one constant in the tabloid journalist cliché construct, it is their cynicism. But I took it to heart, and it has served me well. Because it is easy, very easy, to become cynical as a journalist. News happens again and again. Same sort of thing, just different players/victims/corpses. Cynicism is easy, it is common… and it is fatal. The cynical journalist has no spark, no edge, no drive.

That is true for journalists. And it is true for speechwriters.

If you believe the world is rotten, you are right, because it rots for you.

Sadly, it rotted for George Lee Walker.

I say that we should always hold on to the fact that there can be redemption, even from bad situations, bad speechwriting gigs. A way to find meaning, purpose and hope. But that requires us to reject, and keep rejecting, our inner cynic.

That is not always possible, I know. There are terrible, hopeless speechwriting jobs out there… just like there are dreadful journalism role and grim jobs in any walk of life you can imagine. But, if it is that bad, don’t stay. It is the cynic inside you that says there is nothing better out there… the cynic that kills you.

In writing this, a lyric from one of my favourite songs came to me: F.E.E.L.I.N.G.C.A.L.L.E.D.L.O.V.E. by the marvellous Sheffield band Pulp.

The narrator is gripped by stasis, and talks of, “the same events… shuffled in a slightly different order… each day… just like a modern shopping centre”. He is George Lee Walker transported into nasty, unheated social housing in the north of England.

His cynicism is punctured by love.

We can choose to puncture our own cynicism, through love of and for the world… and all the wonders it holds in it.

My thanks to Colin Myler for teaching me that.

***

Postscript: One more veteran corporate speechwriter weighs in:

So I’ve ordered my copy off ebay. But I have to tell you – anon, of course – that some of the descriptions you shared all ring as true to me today as when they were published.

The long periods of guilty downtime. The silence (amplified even more because of technology and – today – COVID). The speechwriter emeritus declaring, “it’s all been said.”

That last one is particularly true-ish. The corporate world mostly has a short memory. Very few people have enough tenure to actually know what was said 5, 10, 15, 20 years ago. Even if they were there, they were so busy just trying to march through bureaucratic sludge of everyday corporate work that they weren’t paying attention to the corporate rhetoric. So to them, everything is a new trend, a hot topic, an opportunity to ‘ride this social media trend.’

But I’m nearly in my third decade of speechwriting and I know. I know I could pull out a speech I wrote 20 years ago – after updating the writing with the superior skills I’ve learned from The Speechwriting School, of course – and send it up and out into the world and few would know the difference. The speech topics, the challenges we describe and – depressingly – the solutions we propose, are all very familiar.

Economic forecasts? Check. State of the Industry? Check. Stakeholder engagement? Check. Ethics as a corporate virtue? (Cough). Check. I was writing VSOTD speeches on that 20 years ago.

So, yes, much of it has all been said. BUT … here’s what an experienced speechwriter also knows.

First, every now and then the topics are new. Writing about race? Most corporations would roll out one speech a year to ‘celebrate’ Black History Month (the CEO would do it one year but a VP would do it the next, lest the masses think you’re obsessed with race). Today I’m writing about racial and ethnic injustice and the connections between our business and those systemic issues. Because much of the political world is caught in divisive stalemate, it feels like corporations are being tasked with taking the lead on big issues like climate change and race and, even, civility. That’s new. Not exactly a hopeful trend (after all, we paid good money for our politicians and we expect them to do our bidding) but at least for the speechwriter it’s not busting the same rocks in the same quarry day after day.

Second, just because much of it has already been said doesn’t mean it’s all been heard, especially by today’s audience. It’s mostly old news, except to those who need to hear it most – the ones who have an opportunity now – if they listen – to do something about it.

So, third, if you’re not too jaded and bitter and cynical by your second (or third) decade as a writer, you know your skills are just as important today as they were 20 years ago. In fact, I’d argue they’re probably more valuable. It’s harder and harder to get your point of views out and to be heard above the TikTokers, the Instagramers and the Tweeters. The topics are very familiar, but our approach is different today than it was 20 years ago in terms of language and structure and cadence.

So, yes, as Lech says, it’s easy to get cynical. I’ve spent time in that camp, too. Then, again, I’ve done some of my most important and impactful work over the past 12 months. It’s not The Future is Tomorrow stuff (writing that would signal the end is near), but it’s valuable, especially to the audience who desperately needs to hear the boss’s words – again and again – that we’ll get through this.

It’s enough to give even the most disillusioned speechwriter some hope.