Speechwriting elder, respect thyself

June 17, 2021

Aged, erudite wisdom is unfashionable, by definition. Then why is it my life's goal to one day be as cool as Jerry Tarver?

It’s an unkept secret among speechwriters that if you want to talk to the head of the Professional Speechwriters Association, all you have to do is email me and ask. Whether you are a PSA member or not. In fact, whether you are a speechwriter or not!

I keep this policy because I often learn something on these calls, and make lasting connections. And because I like being helpful. And because there have been people who spoke with me at lonely or scary or confusing times in my career and gave me their warm and generous counsel.

But as I note with a start that I’m in my sixth decade of life on this planet, I’m adding “frank” to that list of modifiers.

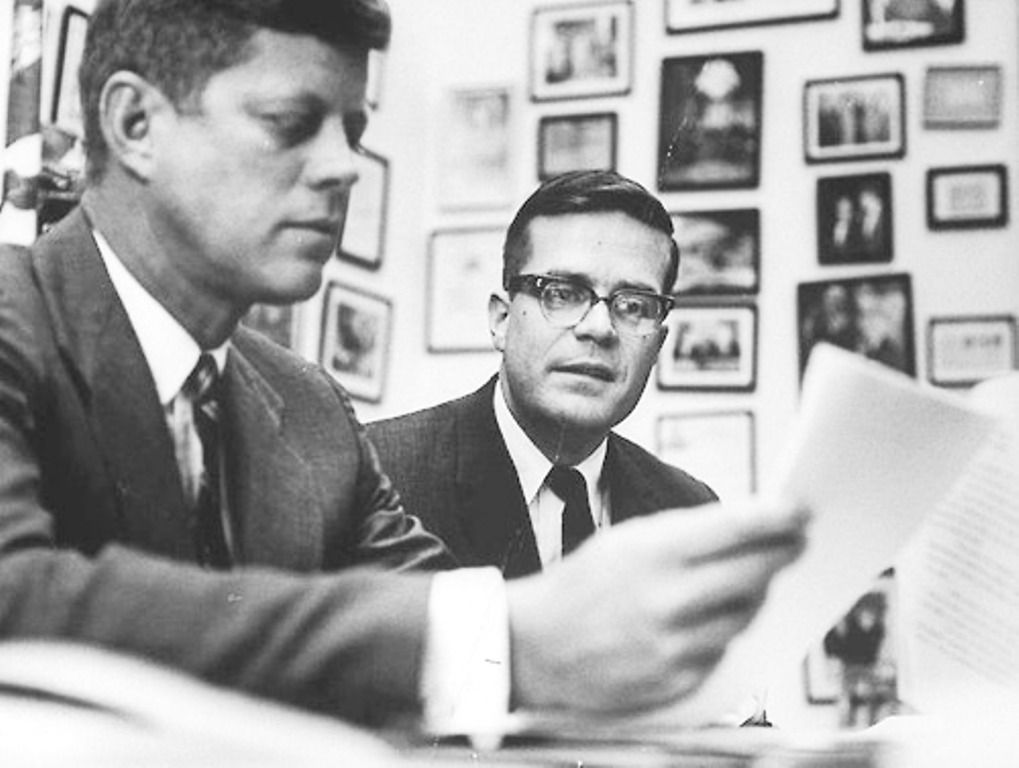

I remember passing on an emailed question to speechwriting guru emeritus Jerry Tarver some years ago—somebody’s question about the science of why the “rule of three” seemed to work so well, in rhetoric. The consummate southern gentleman drew on a whole life of university rhetoric scholarship and three decades of teaching workshops to working speechwriters to tell me that anyone who would ask such a question would fall for any fool pop-psychological answer that came down the pike. (Which seemed uncomfortably like it also applied to someone who would pass on such a question.)

Though I haven’t his scholarly erudition to stand upon—a dozen years ago, Tarver donated his 3,000-book collection of rhetoric tomes to Ohio State University, I’m starting to feel like Jerry Tarver, just a little bit. It’s been almost a decade since I founded the Professional Speechwriters Association—and three decades since I started hanging around speechwriters—and if people ask me questions, they’re going to hear the truth.

“How do I break into corporate speechwriting, at age 26?” I don’t know, how do I break into professional football, at 52? Also, why are you in such a hurry to give your precious young voice away to put words in the mouth of some old gaffer? If you can give me a compelling answer to that question, you’ll probably have your answer to your own question.

That sort of thing.

“Why am I not getting ahead in my job?” I don’t know, but I bet you do. For instance, if I called you out of the blue and asked, “Why aren’t you getting ahead in your job?” I bet you’d have answers, and I bet they’d be right.

“How can I write compelling speeches for a leader who won’t tell me what they want to say?” You can’t, baby! Content yourself to write pleasant blather for ribbon cuttings, or find a new job, writing for someone who actually does give a shit. Next!

“The speaker I work for has no arms and no legs, but insists upon using a lectern. What should I do?”

I don’t want to be a jerk. I don’t want to come off like Fran Lebowitz. And of course I never will, in person, or on the phone with a living, breathing human being. And I want to keep an open mind to possibility—maybe I can help this person square the circle, if I just think hard enough!

But I also want to take full advantage of my experience to get down to brass tacks faster so we can get more done. I want to waste less time now that I have less time to waste.

And I want to tell the truth, clear as I know it, until I no longer like the sound.

No longer liking the sound—that eventually happened to Jerry Tarver, as a matter of fact.

He quit teaching speechwriting because, he told me, he was tired of hearing his own voice. He retired to his farm in rural Virginia, where he read books, watched baseball on TV and made venison chili for his poker buddies (I was once invited to join them, which was almost as good as actually joining them). And he drove around his property on his own bulldozer. Still does, as far as I know.

“David, can I tell you something?” Jerry once told me. “When you own a bulldozer, every problem looks like something that can simply be pushed over.”

But while Jerry Tarver is pushing things over on his farm, he leaves it to David Murray—and other protégés, like Speechwriting School director Fletcher Dean, who learned at Jerry’s knee in the early ’80s—to advise young writers, gently but frankly.

One of my favorite essays in my own book, An Effort to Understand, laments that older men and women fear being seen as domineering, and “potential teaching situations … turn into bitten tongues concealed by kindly smiles.” I worry: “What if the elders in a society—the elders in our families, our parents’ friends, the old lady at the end of the bar who can see you’re holding the pool stick wrong—don’t dare to share their experience at all?”

The essay’s title: Elder, respect thyself.

***

Postscript: I received a response from the man himself. Jerry Tarver writes:

David,

I enjoyed reading these words of sound advice and enjoyed as well recalling conversations from the good old days.

May I encourage all your readers to aspire to a productive old age? The best model is probably Isocrates (436-338 B.C), a speechwriter and the head of his own school of rhetoric, who taught until he was 85. He was not a great speaker because of a poor voice, but he followed two rules worthy of emulation: charge high fees and work only with talented people.

I am 86, David, and my ancient Kawasaki has probably reached about the same point in bulldozer years. It has just had a radiator hose replaced and chugs merrily on. I find that shoving 35 pine trees into a compact pile has nearly the satisfaction of writing a good declarative sentence.