Specter’s last salvo

December 20, 2010

This is not a farewell address, but rather a closing argument to a jury of my colleagues and the American people outlining my views on how the Senate—and with it, the Federal Government—arrived at its current condition of partisan gridlock, and my suggestions of where we go from here on that pressing problem and key issues of national and international importance.

To make a final floor statement is a challenge. The Washington Post noted the poor attendance at my colleagues’ farewell speeches earlier this month. That is really not surprising since there is hardly anyone ever on the Senate floor. The days of lively debate with many members on the floor are long gone. Abuse of Senate rules has pretty much stripped senators of the right to offer amendments. The modern filibuster requires only a threat and no talking. So the Senate’s dominant activity for more than a decade has been the virtually continuous drone of the quorum call.

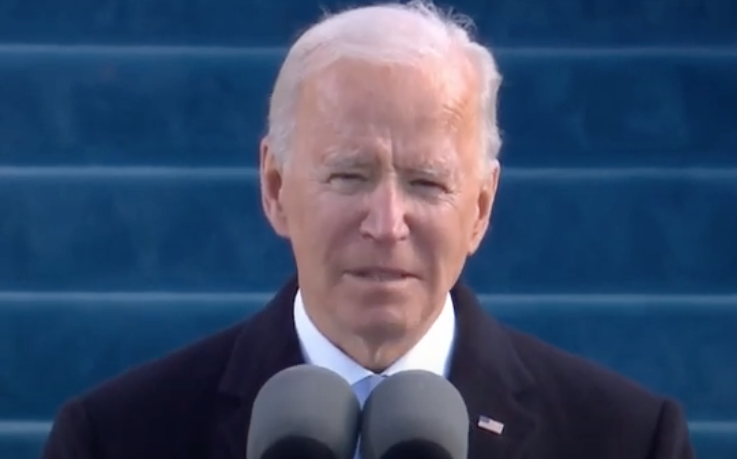

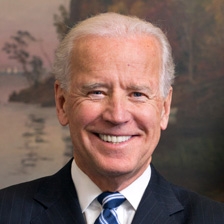

But that is not the way it was when I was privileged to enter the world’s greatest deliberative body 30 years ago. Senators on both sides of the aisle engaged in collegial debate and found ways to find common ground on the nation’s pressing problems. When I attended my first Republican moderates luncheon, I met Mark Hatfield, John Chaffee, Ted Stevens, Mac Mathias, Bob Stafford, Bob Packwood, Chuck Percy, Bill Cohen, Warren Rudman, Alan Simpson, Jack Danforth, John Warner, Nancy Kassenbaum, Slade Gorton, and others—a far cry from later years when the moderates could fit into a telephone booth. On the other side of the aisle, I found many Democratic senators willing to move to the center to craft legislation: Scoop Jackson, Joe Biden, Dan Inouye, Lloyd Bentsen, Fritz Hollings, Pat Leahy, Dale Bumpers, David Boren, Russell Long, Pat Moynihan, George Mitchell, Sam Nunn, Gary Hart, Bill Bradley, and others.

They were carrying on the Senate’s glorious tradition. The Senate’s deliberate, cerebral procedures have served our country well. The Senate stood tall in 1805 in acquitting Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase in impeachment proceedings to preserve the independence of the federal judiciary. The Senate stood tall in 1868 to acquit President Andrew Johnson in impeachment proceedings that preserved the power of the Presidency. Repeatedly, in our-223 year history the Senate has cooled the passions of the moment to preserve the institutions embodied in our Constitution which have made the United States the envy of the world.

It has been a great privilege to have had a voice for the last 30 years in the great decisions of our day: how we allocate our resources among economic development, national defense, education, environmental protection and NIH funding; the Senate’s role in foreign policy; the protection of civil rights; balancing crime control and defendants’ rights; and how we maintained the quality of the federal judiciary—not only the high profile 14 Supreme Court nominations that I have participated in but the 112 Pennsylvanians who have been confirmed during my tenure in the District Courts or Third Circuit.

On the national scene, top issues are the deficit and national debt. The Deficit Commission has made a start. When raising the debt limit comes up next year, that may present an occasion to pressure all parties to come to terms on future taxes and expenditures to realistically deal with these issues.

Next, Congress should act to try to stop the Supreme Court from further eroding the Constitutional mandate of separation of power. The Court has been eating Congress’s lunch by invalidating legislation with judicial activism after nominees commit under oath in confirmation proceedings to respect Congressional fact finding and precedents. The recent decision in Citizens United is illustrative. Ignoring a massive Congressional record and reversing recent decisions, Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Alito repudiated their confirmation testimony and provided the key votes to permit corporations and unions to secretly pay for political advertising—effectively undermining the basic democratic principle of the power of one person/one vote. Roberts promised to just call balls and strikes and then moved the bases.

Congress’s response is necessarily limited in recognition of the importance of judicial independence as the foundation of the rule of law. Congress could at least require televising the court proceedings to provide some transparency to inform the public about how the Court is the final word on the cutting issues of the day in our society. Brandeis was right that sunlight is the best disinfectant. The Court does follow the election returns and does judicially notice societal values as expressed by public opinion. Polls show 85% of the American people favor televising the Court when told that a citizen can only attend an oral argument for three minutes in a chamber holding only 300 people. Great Britain, Canada, and state supreme courts permit television.

Congress has the authority to legislate on this subject just as Congress decides other administrative matters like what cases the Court must hear, time limits for decisions, the number of justices, the day the Court convenes and the number for a quorum. While television cannot provide a definitive answer, it could be significant and may be the most that can be done consistent with life tenure and judicial independence.

Additionally, I urge Congress to substantially increase funding for NIH. When NIH funding was increased from $12 to $30 billion annually, and $10 billion added in the stimulus package, significant advances were made on medical research. It is scandalous that a nation with our wealth and research capabilities has not done more. Forty years ago, the President of the United States declared war on cancer. Had that war been pursued with the diligence of other wars, most forms of cancer might have been conquered.

I also urge my colleagues to increase their activity on foreign travel. Regrettably, we have earned the title of “The Ugly Americans” by not treating other nations with proper respect and dignity. My experience in Codels to China, Russia, India, NATO, Jerusalem, Damascus, Bagdad, Kabul and elsewhere provided the opportunity for eyeball-to-eyeball discussions with world leaders about our values, our expectations and our willingness to engage in constructive dialogue. Since 1984, I have visited Syria almost every year. My extensive conversations with Hafiz al-Assad and Bashar al-Assad have convinced me that there is a realistic opportunity for a peace treaty between Israel and Syria if encouraged by vigorous U.S. diplomacy. Similar meetings with Muammar Ghaddafi, Yasser Arafat, Fidel Castro, Saddam Hussein and Hugo Chavez have persuaded me that candid, respectful dialogue with our toughest adversaries can do much to improve relations among nations.

And now let me shift gears—in my view, a principle reason for the historic stature of the United States Senate has been the ability of any Senator to offer virtually any amendment at virtually any time. The Senate Chamber provides the forum for unlimited debate with the potential to acquaint the people of America and the world about innovative proposals on public policy and have a vote on the issue.

Regrettably, that has changed in recent years because of abuse of the Senate rules by both parties. The Senate rules allow the Majority Leader, through his right of first recognition, to offer up a series of amendments to prevent any other senator from offering an amendment. That had been done infrequently up until about a decade ago and lately has become a common practice by both parties.

By precluding other Senators from offering amendments, the Majority Leader protects his party colleagues from taking tough votes. Never mind that we were sent here and paid to make tough votes. The inevitable and understandable consequence of that practice has been the filibuster. If a Senator can not offer an amendment, why vote to cut off debate and go to final passage? Senators were willing to accept the will of the majority in rejecting their amendments, but unwilling to accept being railroaded to concluding a bill without an opportunity to modify it. That practice led to an indignant, determined minority to filibuster and deny the 60 votes necessary to cut off debate. Two years ago on the Senate floor, I called the practice “tyrannical.”

The decade from 1995-2005 saw the nominees of President Clinton and President Bush stymied by the refusal of the other party to have a hearing or floor vote on many judicial and executive nominees. Then in 2005, serious consideration was given by the Republican Caucus to changing the long standing Senate filibuster rule by invoking the so called “nuclear” or “constitutional option.” The plan called for Vice President Cheney to rule 51 votes were sufficient to impose cloture for confirmation of a judge or executive nominee. His ruling, challenged by Democrats, would then be upheld by the traditional 51 votes to uphold the Chair’s ruling.

As I argued on the Senate floor at that time, if Democratic Senators had voted their conscience without regard to party loyalty, most filibusters would have failed. Similarly, I argued that had Republican Senators voted their consciences without regard to party loyalty there would not have been 51 of the 55 Republican Senators to support the nuclear option.

The Majority Leader scheduled the critical vote for May 25, 2005. The outcome of the vote was uncertain with key Republicans undeclared. The showdown was averted the night before by a compromise by the so called “Gang of 14”. Some nominees were approved, some rejected, and a new standard was established to eliminate filibusters unless there were “extraordinary circumstances” with each senator to decide whether that standard was met. That standard has not been followed as those filibusters have continued in recent years. Again, the fault rests with both parties.

There is a way out of this procedural gridlock by changing the rule on the power of the Majority Leader to exclude other Senators’ amendments. I proposed such a rule change in the 110th and 111th Congresses. I would retain the 60 vote requirement for cloture on legislation with the condition that Senators would have to have a talking filibuster—not merely the present notice of intent. By allowing senators to offer amendments and a requirement for debate, not just notice, I think filibusters could be effectively managed as they had been in the past and still be retained where necessary to give adequate debate on controversial issues.

I would change the rule to cut off debate on judicial and executive branch nominees to 51 votes as I formally proposed in the 109th Congress. Important positions are left open for months including judicial nominees with emergency backlogs. Since Judge Bork and Justice Thomas did not provoke filibusters, I think the Senate can do without them on judges and executive office holders. There is a sufficient safeguard of the public interest by requiring a simple majority of Senators on an up/down vote. I would also change the rule requiring 30 hours of post-cloture debate and the rule allowing the secret “hold” which requires cloture to bring the matter to the floor. Requiring a senator to disclose his “hold” to the light of day would greatly curtail this abuse.

While political gridlock has been facilitated by the Senate rules, partisanship has been increased by other factors. Senators have gone into other states to campaign against incumbents of the other party. Senators have even opposed their own party colleagues in primary challenges. That conduct was beyond contemplation in the Senate I joined 30 years ago. Collegiality can obviously not be maintained when negotiating with someone simultaneously out to defeat you, especially within your own party.

In some quarters, “compromising” has become a dirty word. Some senators insist on ideological purity as a precondition. Senator Margaret Chase Smith of Maine had it right when she said we need to distinguish between the compromise of principle and the principle of compromise. The Senate itself was created through the so-called “Great Compromise,” in which the framers decreed that states would be represented equally in the Senate and proportionate to their populations in the House. As Senate historian Richard Baker wrote, “Without that compromise, there would likely have been no Constitution, no Senate, and no United States as we know it today.”

Politics is no longer the art of the possible when senators are intransigent in their positions. Polarization of the political parties has followed. President Reagan’s “Big Tent” has frequently been abandoned by the Republican Party. A single vote out of thousands cast by an incumbent can cost his seat. Senator Bob Bennett was rejected by the far right in his Utah primary largely because of his vote for TARP. It did not matter that Vice President Cheney had pleaded with the Republican caucus to support TARP or President Bush would become a modern Herbert Hoover. It did not matter that 24 other Republican Senators out of 49 also voted for TARP. Senator Bennett’s 93% conservative rating was insufficient. Senator Lisa Murkowski lost her primary in Alaska. Congressman Mike Castle was rejected in Delaware’s Republican primary in favor of a candidate who thought it necessary to defend herself as not being a witch. Republican senators contributed to the primary defeats of Bennett, Murkowski and Castle. Eating or defeating your own is a form of sophisticated cannibalism. Similarly, on the other side of the aisle, Senator Lieberman could not win his Democratic primary.

The spectacular re-election of Senator Lisa Murkowski on a write-in vote in the Alaskan general election and the defeat of other Tea Party candidates in 2010 in general elections may show the way to counter right-wing extremists. Arguably, Republicans left three seats on the table in 2010—beyond Delaware, also Nevada and arguably Colorado—because of unacceptable general election candidates. By bouncing back and winning, Senator Murkowski demonstrated that a moderate/centrist can win by informing and arousing the general electorate. Her victory proves that America still wants to be and can be governed by the center.

Repeatedly, senior Republican senators have recently abandoned long held positions out of fear of losing their seats over a single vote or because of party discipline. With 59 votes for cloture on the Democratic side of the aisle, not a single Republican would provide the 60th vote to advance legislation on key issues such as identifying campaign contributors.

Notwithstanding the perils, it is my hope that more senators will return to greater independence in voting and crossing of party lines evident thirty years ago. President Kennedy’s “Profiles in Courage” shows the way. Sometimes party does ask too much. The model for an elected official’s independence in a representative democracy was articulated in 1774 by Edmund Burke of the British House of Commons, who said: “his [the elected representative’s] unbiased opinion, his mature judgment, his enlightened conscience…[including his vote] ought not to be sacrificed to you, to any man or any set of men living.”

Above all, we need civility. Steve and Cokie Roberts, distinguished journalists, put it well in a recent column: “Civility is more than good manners . . . Civility is a state of mind. It reflects respect for your opponents and for the institutions you serve together. . . This polarization will make civility in the next Congress more difficult—and more necessary—than ever.”

A closing speech has an inevitable aspect of nostalgia. An extraordinary experience has come to an end. But my dominant feeling is pride in the great privilege it has been to be a part of this unique body with colleagues who are such outstanding public servants. I have written and will write elsewhere about my tenure here, so I do not say “farewell” to my continuing involvement in public policy, which I will pursue in a different venue. I leave with great optimism for the future of our country and the continuing vital role of the United States Senate in the governance of our democracy.