Pregiarized!

September 18, 2025

In which two 19th-century gasbags co-opt my dueling theories on how to help speakers be more compelling—in arrears!

There’s nothing new under the sun. (That’s an old saying too.)

For years, I’ve been telling speechwriters there are two ways to coach speakers into becoming more dynamic, authentic and persuasive on stage.

First, you hire a professional speaking coach—often a member of the diaspora of former actors—to teach the boss where how to stand and what to do with her hands. Basically, acting techniques that will help her appear as if she’s as genuinely comfortable at a lectern as she is at her dinner table yelling at her kids.

Or, you can write speeches on and around the subjects that happen to truly animate that leader—the emotional forces that either pushed or pulled her to her position of power, and the intellectual passions that make her truly believe her work and her life have meaning to the audience she’s speaking to.

Because I find the second scenario much more worthy of a life’s study than the former, I favor it naturally—and adamantly.

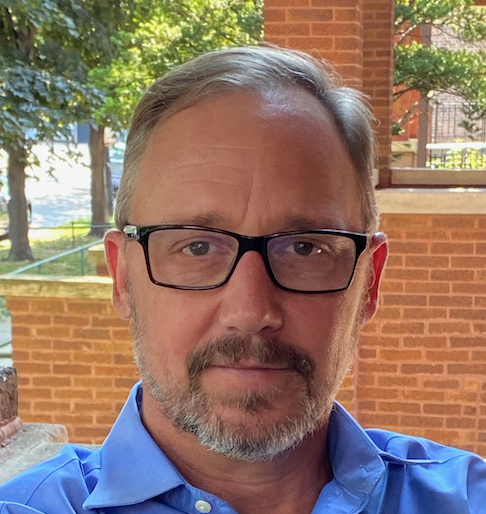

For most of the last couple of decades, I thought this coaching-versus-content dichotomy was my unique observation. But chatting with the scholarly speechwriter Stephen McKenna the other day, I learned the other day that it arose (at the latest) from the conflicting oratorical philosophies of an Irish teacher and clergyman named Gilbert Austin and a French singer and orator named François Delsarte. Like, more than 200 years ago.

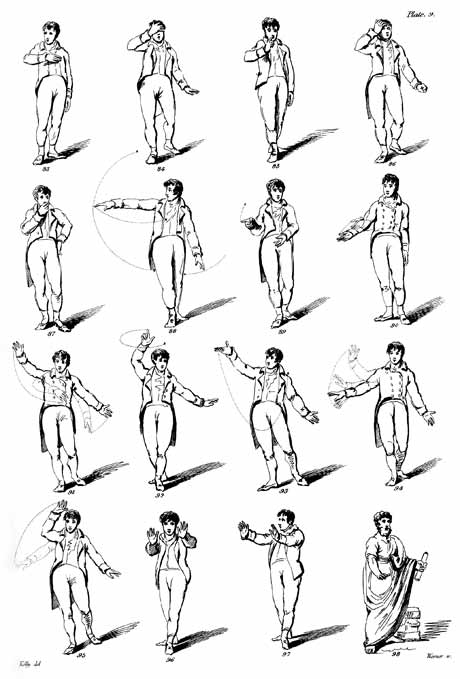

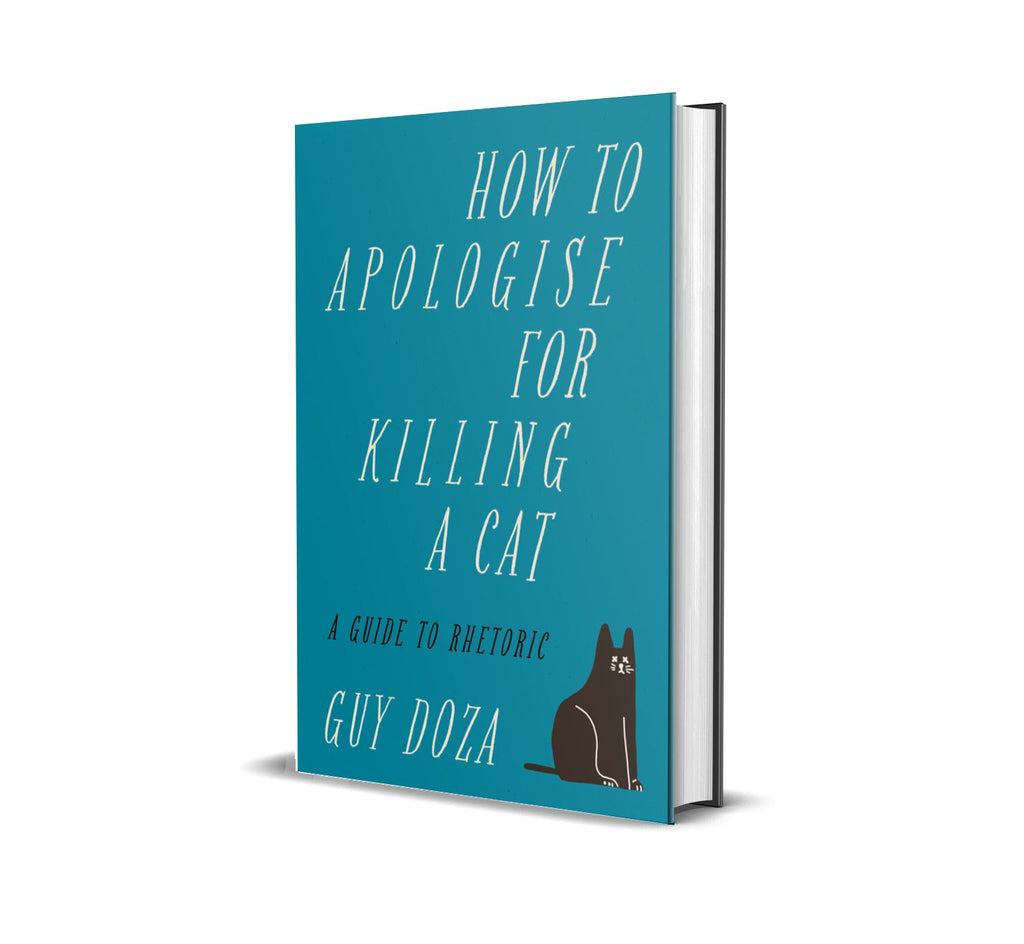

Austin essentially believed in the first method of oratory. In his 1806 book, Chironomia, or a Treatise on Rhetorical Delivery, Austin sought to teach speakers how to move their bodies, and “what it expressively means to move forward, backward, to the side,” and “what it means to speak within the world of discourse which the gestural sphere subscribes.”

Stuff like this, which some speaking coaches still teach today.

Delsarte, on the other hand, believed that the speaker’s body didn’t even exist in the equation, except as an expression of the speaker’s spirit. If the speaker is communicating that spirit honestly to an audience that can hear it, the speaker’s body will do what it must to get the ideas across. “Man does not hold the center at all,” Delsarte said, “for that space is ever the divinity’s.”

Okay, so I’m not an original thinker on orator, after all. Just an old-school dyed-in-the-wool Delsartian, as it turns out.

Look, I don’t mind standing on the shoulders of giants. But I don’t appreciate giants slipping their shoulders under my feet while I’m busy gassing on about modern rhetoric.

Ha, great piece, David. Thanks for the shout-out.

I kind of love Austin’s quirkiness and his wonderfully wrongheaded technologization of the body. He was man of the early industrial age, when the smart people thought everything should be reducible to code of reference or a predictable mechanism. It was kind of prescient when you look at how early 20th century comms theorists adopted simplistic sender-receiver models–like Shannon and Weaver’s, which was designed to study noise in early telephone systems. “Information” was a measurement of predictability of the signal, not meaning. Not going to work for oratory!

There’s also a kind of dark politics shadowing this–as if physical delivery is the means of directly controlling the audience, like marionettes. Austin’s diagrams always make me think of Hitler practicing his gestures in front of a mirror and having himself photographed so he could study the pics (https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/hitler-rehearsing-speech-front-mirror-1925/).

Delsarte wanted an exact science too, but much more my kind of guy. Les grands esprits se rencontrent!

Yes, Austin is the Frederick Taylor or oratory. Who knew? (You!)