Speechwriting: Still a Marvelous Job for a Moonlighter

August 05, 2021

Speechwriting guru Bob Lehrman asked speechwriting guru David Murray why speechwriters don't write novels anymore, on the side. The two discovered: Many do!

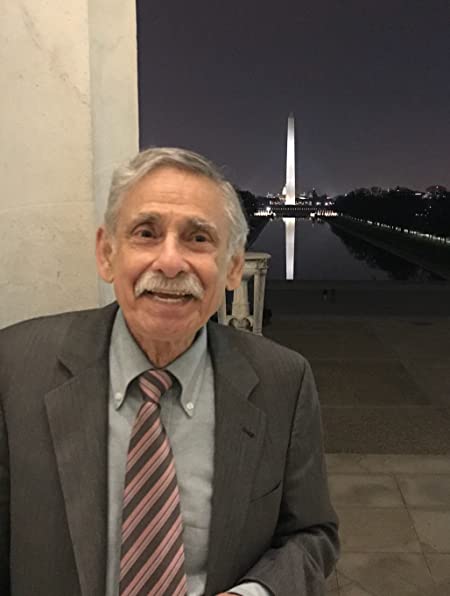

Professional Speechwriters Association chief David Murray got a question awhile back from a guy who normally has the answers—speechwriting sage Robert Lerhman, co-author of The Political Speechwriter’s Companion, speechwriting teacher at American University, Johns Hopkins and the PSA’s Speechwriting School—and author of many novels and other bylined works a fifty-year career that began at the Iowa Writers Workshop, under the tutelage of a then-obscure Kurt Vonnegut.

“Question for you,” Lehrman wrote, mentioning that he’d queried a magazine that caters to people writing novels, stories and poetry but often looking for a way to earn a living while they struggle through that first novel. “Teaching isn’t the only way,” Lehrman wrote. “What about speechwriting as a meaningful way to combine with writing under your own name?”

He continued:

To me Speechwriting has worked well. That is, I treasure my seven books but I also value writing speeches as a way of backing people and causes I support.

But when I tried coming up with writers who have combined speechwriting and serious writing, I almost drew a blank. … [Here he named a few of our colleagues.]

There’s a long list of writers who wrote speeches until their books sold—Salman Rusdhie, William Kennedy, Dick Yates. But not after.

Am I unusual? I would still write the piece but I’d rather not write as if I’m the only one. What’s the truth? Would you know?

Murray replied that speechwriters who moonlight under their own name, pursuing their own simultaneously sustainable careers in speechwriting and other careers are exceptions. Here’s why, Murray said:

I agree that moonlighting writers are more of a thing of the past. My dad worked with Elmore Leonard at an advertising agency in Detroit, and “Dutch,” as they all called him, would work on his early novels early in the morning and then put the pages in the drawer and get busy writing copy for Chevrolet—and maybe be caught working on it during the day, too.

An aged corporate speechwriter told me that back in the 1980s, he would write speeches until 11 a.m., then “kick the office door closed” and do whatever freelance stuff he felt like doing for the rest of the day.

There are no office doors anymore (and maybe not even any drawers).

More to the point, in-house speechwriting jobs are not just speechwriting jobs anymore. They are all-consuming executive communication jobs that take far too much out of most of their practitioners to allow for creative writing around the edges (with all of life’s other demands also nagging). Often, they take too much out to allow for creative speechwriting!

Obviously a freelance speechwriter has more freedom—and conceivably could make a bundle on a few fat speechwriting assignments every year, speechwriting being the most lucrative writing speciality there is—and write books the rest of the time.

I just don’t see it happening.

Maybe part of why is that the field is more professionalized than it was—partly thanks to goons like us—so that when an unknown Yates or Vonnegut or Rushdie turns up looking for a speech assignment, the communications manager wants to know what other speeches they have written, wants to see those clips, maybe even wants to know whether (gasp) they’re a card-carrying member of the Professional Speechwriters Association.

So they throw up their hands and try to find something else to do. I talk to folks like this occasionally, and we always hang up with them sounding discouraged. But what am I going to tell them, that they have every right to take a chunk of [a veteran speechwriter’s] livelihood, just because they want to earn a few bucks on the side while they work on their novel? No, son, get your ass to Speechwriting School, at least!

As we both teach, speechwriters succeed because they are good writers, yes; but they must also be great researchers, great thinkers and committed partners to the speakers they serve and the causes their rhetoric supports. How much of that would William Kennedy have had the patience for?

You’re a unicorn, Bob! And while I could imagine someone as committed to both bylined writing and ghosted stuff as you are (let alone teaching and grading papers!), would-be speechwriter/novelists should be warned that this isn’t a casual craft anymore, or a professional lark.

Murray’s take was corroborated by some—including Splunk CEO comms director Melanie Duzyj, who wrote in part: “Speechwriters ‘just’ acting as speechwriters is of a bygone era, and the craft is quickly evolving to become Executive Communications, a new around-the-clock discipline.”

But it was contradicted by several speechwriters in a lively LinkedIn exchange that curious readers should read.

Speechwriter friends—all communicator friends—what are your thoughts? We’ll share them with Murray and Lehrman, and we’ll all get more astute about how to use speechwriting to support your other writing.