A Beautiful Meeting

February 19, 2019

A few valuable items to declare on my return from the Professional Speechwriters Association's first Asia-Pacific Speechwriters Conference, in Sydney

A professional conference is daunting to describe and, unless it has been a comical disaster, depressing to read about. So I'll neither go on long nor try to tell you everything about an event that was ultimately a greater success than any of its organizers hoped for. (Yes, I know: how dull.)

But one who is willing to further dirty the atmosphere with jet fuel fumes in order to convene an international gathering owes at least a brief report—if not on everything that went down Down Under, at least on what one will bring back.

Some souvenirs from Sydney:

There is no such thing as Asia-Pacific speechwriting. Writers believe that if they describe a thing in words, the thing is obligated to exist. Then they arrive at their "first-ever Asia-Pacific Speechwriters Conference," and discover that it is actually the first-ever Australian Speechwriters Conference with One Brilliant Maori. Subtitle: Mostly government scribes, from the capital city of Canberra.Which is absolutely fine, of course—especially since there are three dozen of them—who, along with the speakers you've invited, make the sort of heaving human hive from which an actual community might alight.

These were happy days of fascinating conversation (and frequently funny, as Aussies have a limited tolerance for unleavened earnestness)—in a setting so culturally rich, at the State Library of New South Wales, that no one wondered why people from other points in the Pacific Rim made the trip. Next time, we hope.

Meanwhile, there now is, where there was not before, a nascent speechwriting community in Australia—and, to hear Kiwi leadership communication doyenne Christine Ammunson tell it, a gathering interest in New Zealand, too.

Judging from this sample, Australian speechwriters who speak are quietly erudite—and it's a good thing, because the speechwriters who listen are politely skeptical. Indeed, these speechwriters said that Aussie audiences in general pride themselves on their show-me stance. Happily, our speakers had much to show. And: After three days of rhetorical bombardment and communication, more than a few seemed to have specks of their own flint in their eyes at the end of my capnote show of moving speeches from history.

My sentimental American self was moved from the jump—by my own introduction of keynote speaker Don Watson, an author of many great books and the former speechwriter to legendary Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating. I played a clip from Keating's landmark Red Fern Park speech, delivered in 1992—and realized to my astonishment that its writer had never seen it before, including on the day, when he hadn't attended. Watson later said he was amazed at how the distracted and perhaps intentionally disruptive indigenous audience came immediately to quiet and stunned attention when Keating began to take unprecedented responsibility, on behalf of the Europeans, for the decimation of aboriginal culture.

Watson had more to say: He told a shaggy dog story that culminated in jesting advice for speechwriters, to refer to embrace the scornful labels of jealous or suspicious rivals—he himself was once referred to as "chief ideologist" of the the Labour Party—in hopes of being seen as an evil genius by those on your side, and being given a quiet suite in which to write.

"Speech is the midwife of thought," Watson said more seriously, adding that "there is a poetic key to reality."

And on the subject of poetry and reality, the Sydney poet Mark Tredinnickadvised speechwriters to fill their speeches with "words that have a life outside work." He quoted the poet Philip Levine: "So many poems begin where they should end, and never end." Speeches too, as Tredinnick didn't need to point out.

And the American speechwriter-turned-speaking coach-turned leadership coach Dain Dunston articulated the speechwriter's floating anxiety: Most speechwriters fell into speechwriting, Dunston said, "and they don't know where they'll fall next."

And so on and so forth, point and counterpoint, call and response, over coffee and cocktails over three buzzing days.

There is something new under the speechwriting sun—or something newly named, anyway. Bob Lehrman, author of the Political Speechwriters Companion, has been for many years teaching a technique he calls "the four-part close." He doesn't like the name, because it isn't catchy enough—not as even as catchy as Monroe's Motivated Sequence, a speech structure Lehrman has also taught since Alan P. Monroe was actually living.

With proper casual humor, the second-day keynoter Lehrman publicly mused that perhaps the four-part close might be named more mellifluously—and perhaps after himself.

What about "Lehrman's Landing"? I thought to myself, and determined to run this by Lehrman later.

A bit later, the American leadership communication coach Dain Dunston stood up in front of the whole conference and suggested, "What about Lehrman's Landing?"

And so all that's left to decide is: Will "Lehrman's Landing" be remembered as Dunston's Designation, or Murray's Moniker?

"That's a thorny question," Lehrman lamented.

Speaking of writers' egos, mine was inflated inordinately during the conference cocktail party, when Diana Elliott, managing director of the Melbourne-based leadership communications consultancy Resonance Communications, told me she had read my July 4, 2018 essay on Medium.com, "An American prayer: In conversation with my dead father"—and shared it on Facebook because it was one of the "best things I've ever read."

I'm here to tell you: To travel to the other side of the planet and to have a thoughtful human being there tell you she loved a piece of your writing that you also loved—especially after two glasses of wine—such a conversation can make a fellow's evening.

Lucinda Holdforth—and fifth and sixth and seventh. This was quite a week for the veteran government, corporate and independent speechwriter. On Monday evening, Lucinda held forth at the launch party of her new Harper-Collins book Leading Lines: How to Make Speeches that Seize the Moment, Advance Your Cause and Lead the Way.

The skyscraper soiree was studded with journalistically, artistically, civically and intellectually swanky Sydneysiders, as well as a few guests from America, of which the PSA's Benjamine Knight and I were very lucky to be two.

Then Tuesday and Wednesday, Lucinda presided as the chair of our conference, which she had made possible in a hundred ways, only about half of which I likely know about. (Benjamine and I had had some worries we didn't tell her about, either.)

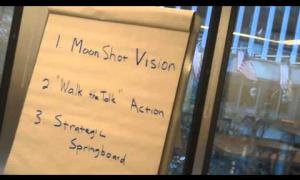

No one told Lucinda that conference chairs don't provide real intellectual content to the event, so she delivered a bracing session on how mistrusted leaders of discredited institutions must "seriously fire up" their rhetoric to counteract widespread doubts about their messages and more effectively defend their arguments. "Choose to divide," she advised counter-conventionally. "Make clear what side you are on, and why. It clarifies your argument and helps followers identify themselves."

And it was a few lines from Leading Lines that helped me bring the conference to a rousing conclusion with a speechwriter's sermon about why we still give ancient speeches in an age when there are infinitely more efficient ways to communicate.

"Perhaps it is because there is some rough magic in the communal experience of listening, and a grace that comes with giving the individual the opportunity to speak their considered thoughts aloud in the welcoming presence of others," I read from Lucinda's book. "We come together to breathe in tandem, to experience our own responses and feelings alongside each other—and sometimes, if we are lucky, and if the speaker speaks truly, in deep connection with each other."

And that's how it felt this week, on the other side of a world that seems a little smaller to me now—and prettier, too.