Some old activists in my neighborhood tell a story from forty years ago, when Pizza Hut was tearing down a historic corner building to put in one of its cheesy restaurants. In response to neighborhood protests, the Pizza Hut PR guy said, “This neighborhood is lucky that Pizza Hut wants to come here.”

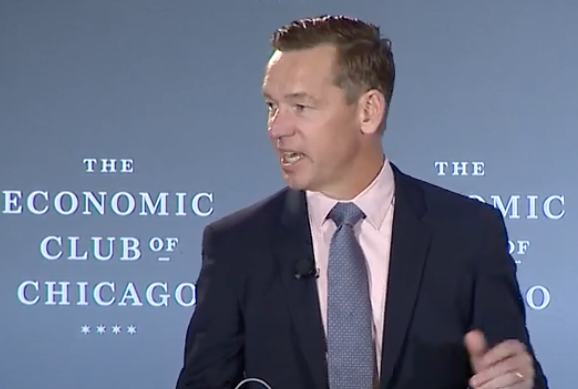

McDonald’s is headquartered here in Chicago. Last week its CEO, Chris Kempczinski, gave a speech at the Economic Club of Chicago, in which he delivered a message that landed similarly on my proud Chicago ears.

Prepare to read a reaction beyond the cool calculus of my occasional professional role as an analyst of corporate rhetoric—but maybe for that very reason, generating some special insight into how corporate CEOs sound to non-corporate audiences.

In the speech, Kempczinski, in this order:

• Reviewed the company’s long history in the Chicago area, going back to founder Ray Kroc and his first store, opened in nearby Des Plaines, Ill. “Others may call Chicago the Second City,” Kempczinski said, “but for McDonald’s Chicago has always been first.”

• Reminded his audience that McDonald’s being headquartered in Chicago pumps money into the local economy. During the speech, Kempczinski also pointed out that McDonald’s donated to 40 “neighborhood organizations that provide life skills training and pre-employment support to Chicago youth—primarily youth from the city’s Black and Latinx communities.” (Those donations separately reported to amount to $3.5 million.)

• Complained of being embarrassed about Chicago because of the crime here. “Given the nature of my job, I travel all over the U.S. and around the world. Everywhere I go, I’m confronted with the same question, ‘What’s going on in Chicago?’ While it may wound our civic pride to hear it, there’s a sense out there that the city is in crisis.” (Calling to mind, of course, The Onion‘s headline a few years ago about outsiders’ perceptions: “Chicago Air Now 80 Percent Bullets.”)

• Remarked on how hard it is to get corporate execs to come to Chicago. “The truth is, it’s more difficult today for me to convince a promising McDonald’s executive to relocate to Chicago from one of our other offices than it was just a few years ago.”

• As much as threatened to pull McDonald’s out of Chicago. “I’ve heard from other mayors and governors who have made their case to me for McDonald’s to relocate our headquarters to their cities and states. And if I’m getting those calls, you can be sure other Chicago companies are as well. … McDonald’s commitment to the City of Chicago isn’t corporate altruism. It’s not open-ended and unconditional. As a publicly traded company, our shareholders would never support that.”

• Grumbled about Chicago taxes, which have not gotten significantly worse since McDonald’s moved downtown from suburban Oak Brook, in 2018.

• And then concluded by identifying a “need to rejuvenate the sense of public/private partnership that has defined Chicago for centuries.” To his peers at the Economic Club of Chicago, Kempczinski said: “The final issue is MINDSET. We need a mindset shift. We’re playing defense when we need to be playing offense. Yes, Chicago has issues, and we need to address them. By the way … the same could be said for every major city in America. But Chicago is an incredible city, and we need to celebrate its virtues. We need to find ways to tell our story in a more compelling way. We need people to associate Chicago with growth, innovation, and opportunity and showcase the proof points which happen all around us every single day.”

Does Kempczinski think this speech, which went ’round the world through CNN, Bloomberg, The Wall Street Journaland a dozen other outlets, helped in that effort? It seems he does. “I’m probably the biggest ambassador you’ll find for the city of Chicago,” Kempczinski said during his speech. Perhaps he believes that sounding an alarm among fellow corporate leaders could light a constructive controlled burn under their butts. And perhaps when corporate leaders hear the magic words, “public/private partnership,” they know just who to call and what to do to start restoring order to Chicago.

From where I sit—in a relatively safe neighborhood on the edge of a fairly violent one—I have some pretty deep doubts.

Trading crime statistics is liar’s poker, but nobody would deny that crime is happening more randomly, in Chicago neighborhoods where it seldom had before. A pal was here recently and asked if it was a good idea walk through relatively ritzy River North neighborhood at night; I heard myself tell her, “No, not a good idea.” Last week the great grassroots Chicago reporter Laura Washington recently wrote a piece saying she no longer feels safe riding the CTA after dark. The heretofore obscure son of Mike Royko is running for alderman in my neighborhood, having gained most of his visibility sounding the alarm about carjackings during the crazed COVID quiet.

But even though I make my living with my typing fingers and my mouth, helping people help elite leaders communicate, I do feel much closer to the ground than Kempczinski’s speech sounds. My wife teaches elementary art in one of Chicago’s poorest neighborhoods and she comes home every night looking like she’s gone 15 rounds with Rocky Marciano. With conviction, she says these young children are more in crisis than they ever were. And they were really in crisis when she started teaching on the West Side, 25 years ago. (And also when our friend Betty started teaching on the South Side, 50 years ago.)

So to hear a CEO talk about this human desperation in terms of its effect on executive recruiting—and to hear him call for a rejuvenated “sense of public/private partnership” as a solution to all this—it sounds pretty far-removed, and pretty unrealistic.

On the one hand, it feels a little strange, criticizing this speech. I usually counsel corporate speechwriters to err on the side of provocative communication, on the notion that persuasive, powerful, candid speech is a big part of what leadership is. In fact, I’ll probably run this speech in the magazine we publish, Vital Speeches of the Day. Like it or not, it’s a rare example of a CEO giving a formal speech at a fancy venue that anyone could really disagree with. Surely my reaction to this speech has to do with my being a Chicagoan. Would this have gotten my attention if it was Hewlett-Packard’s CEO running down Palo Alto? Probably not?

But my perspective as a proud Chicagoan disoriented my usual professional detachment, and helped me see how a CEO must consider the rhetorical context in which she or he speaks. And to have a rich CEO of a massive global company expressing the company’s commitment to your city—and then to have him threaten to leave that city in the same breath! And then to have him lauded in The Wall Street Journal for his courage in having “issued a frank warning Wednesday about the city’s crime and social deterioration,” to a group of fellow penthouse-dwellers. It made me mad.

As did the reaction of the Chicago Tribune‘s editorial board: “What Kempczinski had to say from the bully pulpit of running so huge a Chicago-based entity should immediately be taken to heart.”

And that’s what’s flat wrong. Corporate CEOs don’t have a “bully pulpit,” in the sense that presidents and other elected officials do. They have money, they have economic leverage, they have whatever social meaning their brand contains and they have relationships with other powerful people. And it seems to me that everything a CEO says about social issues beyond the scope of their business should be backed up by actions they are able to take, or contributions they are willing to make.

“Can you imagine Chicago without McDonald’s?” Kempczinski asked rhetorically during the speech, before answering, “I cannot.”

I’d like to imagine McDonald’s using its corporate resources and its neighborhood restaurants to become a literal and metaphorical clean, well-lighted, well-paying place for Chicagoans to turn.

Because, that Pizza Hut on that corner? It was torn down years ago and replaced by something else.

***

Postscript: Yesterday McDonald’s took out a full-page ad in the Chicago Tribune, headlined, “Proud of Our Chicago History and Invested in Chicago’s Future.”